When you think about environmentalism and sustainability, what comes to mind? Perhaps it's the image of lush green forests, solar panels glistening in the sun, or even the act of recycling. But, these concepts aren't just buzzwords; it's a practice and a commitment to sustain the use of materials and resources over time to reduce waste.

This summer, my family and I embarked on an extraordinary journey to explore sustainability in one of the most unique ways possible – by living on the Earthship Biotecture campus in Taos, New Mexico. Our home for this adventure was none other than "Area 52," one of the oldest Earthship models. As we settled into this earthen haven, we were about to experience sustainability in a profoundly tangible way.

Earthships are constructed based on six design principles that help contribute to the goal of environmentally sustainable building design:

Building with natural and repurposed materials: Earthships utilize materials such as used tires, cans, bottles, wood, and mud.

Thermal or solar heating and cooling: Earthships heat and cool themselves using thermal mass and solar gain. They do not use of electricity or the burning of fuel to maintain temperature.

Electricity from solar and wind: Electricity is collected using photovoltaic panels and occasionally windmills. Additionally, the electrical requirements of the buildings are minimized through the use of energy efficient lighting and appliances.

Water harvesting: Water is collected from rain and snowmelt in the roof and is then stored in a cistern for future use.

Sewage treatment: Self-contained sewage treatment and water recycling.

Food production: In-home organic food production capability.

"Design Principles". Earthship Biotecture michael reynolds.

View of our small yet efficient kitchen, with neighboring plant cell which included a fig tree, parsley basil and non edible plants.

A Home Rooted in Sustainable Innovation

Earthships are not your typical homes. They are architectural wonders, where sustainability is not an afterthought but the very essence of their design. Imagine a home that doesn't rely on traditional heating or cooling systems, but instead harnesses the power of thermal mass. Earthships are built using natural and recycled materials like earth-filled tires, glass bottles and adobe walls, creating a structure that can passively regulate its temperature.

View of bathroom entrance, kitchen, and cistren(far right) a large pool of water that collects rain water. Once sent through a series of filtration systems, the mechanism provides water for the entire home.

Embracing Sustainability Daily

Our stay in Area 52 coincided with a severe drought and a relentless heatwave. In most circumstances, this would have been a dangerous situation for a family with a small child. However, Earthships are designed to thrive in harmony with nature. The thick walls, filled with earth(dirt packed used tires), act as a natural insulator, keeping the interior cool during scorching days and warm when the temperature drops at night. It was like living in a time-honored Southern grandmother's home – no air conditioning, but an entirely manageable climate.

Living in an Earthship is an immersive experience in resource conservation. Rainwater harvesting systems ensure every drop is cherished. Greywater (water used from the shower, kitchen and bathroom sinks) is recycled and used for watering plants that provide not only shade but sustenance. Within our Earthship, life flourished - two fig trees, two inca berry bushes, a banana tree, and an array of herbs became staples in our daily meals.

The Lessons of Area 52

Overhead on the roof, solar panels captured the sun's energy, powering our lights and appliances with off the grid electricity. This experience instilled in us a deep awareness of resource consumption, fostering a profound awareness of our daily energy consumer habits. Details such as what products you wash your dishes with to what time of the day you charge your electronics, matter immensely to the function and vitality of this living home.

Solar panels and rooftop windows for air flow on top of the Area 52 roof.

This awareness carries tremendous significance for the energy consumers in the home, as it hinges on the fundamental workings of a solar battery system. These systems have finite storage capacities, and once they reach their maximum capacity during the day, the entire dwelling relies solely on the energy amassed until the sun's return.

One of the biggest perks of living in an Earthship is its "off the grid" nature. It operates self-sufficiently, using thermal mass and solar energy to eliminate cooling, heating, and electric costs. This feature became increasingly significant as we observed the challenges faced by our home base of Atlanta, GA in recent months.

Challenges Back Home

Within just the past few months, Georgia has witnessed a steep increase in electricity costs. Metro Atlanta continues to grapple with the consequences of inadequate infrastructure, leading to citywide flooding, power outages, and pipe bursts during extreme weather, which is increasingly frequent. These events have underscored the vulnerabilities of conventional housing and utility systems.

Furthermore, the skilled trades industry is currently facing a labor shortage, making it increasingly difficult to secure professionals for essential home repairs and maintenance. The versatility and self-sufficiency of Earthships, which often require basic carpentry knowledge, offer an appealing alternative in these times.

Pele managing our grey water(water from the sinks and bath) filtration system, including pvc pipes and a panty hose that is used to filter solids before entering the indoor and outdoor planters that grow produce and plants, which help insulate the home.

Returning to a Self Reliant Culture

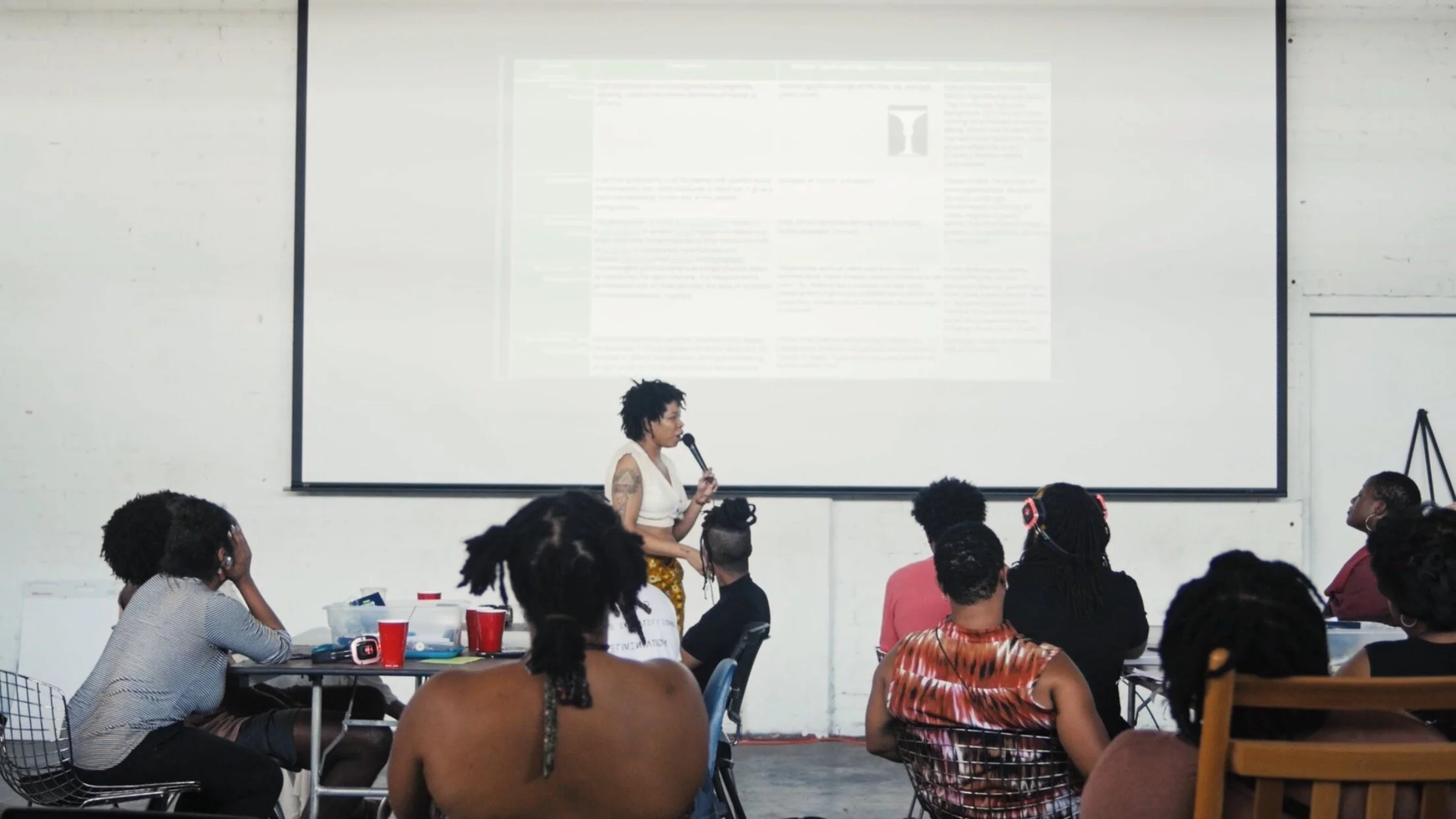

Amidst this immersive experience, I had the privilege of witnessing my partner, Pele, complete his book, "Beyond the Maafa, Reclaiming Our Bodies." This wellness protocol manual is a testament to his dedication, inspired by the health disparities experienced by descendants of the African diaspora, with a special focus on African Americans, capoeira, and the Orisha. It is a work born of passion and a commitment to improving the well-being of our community.

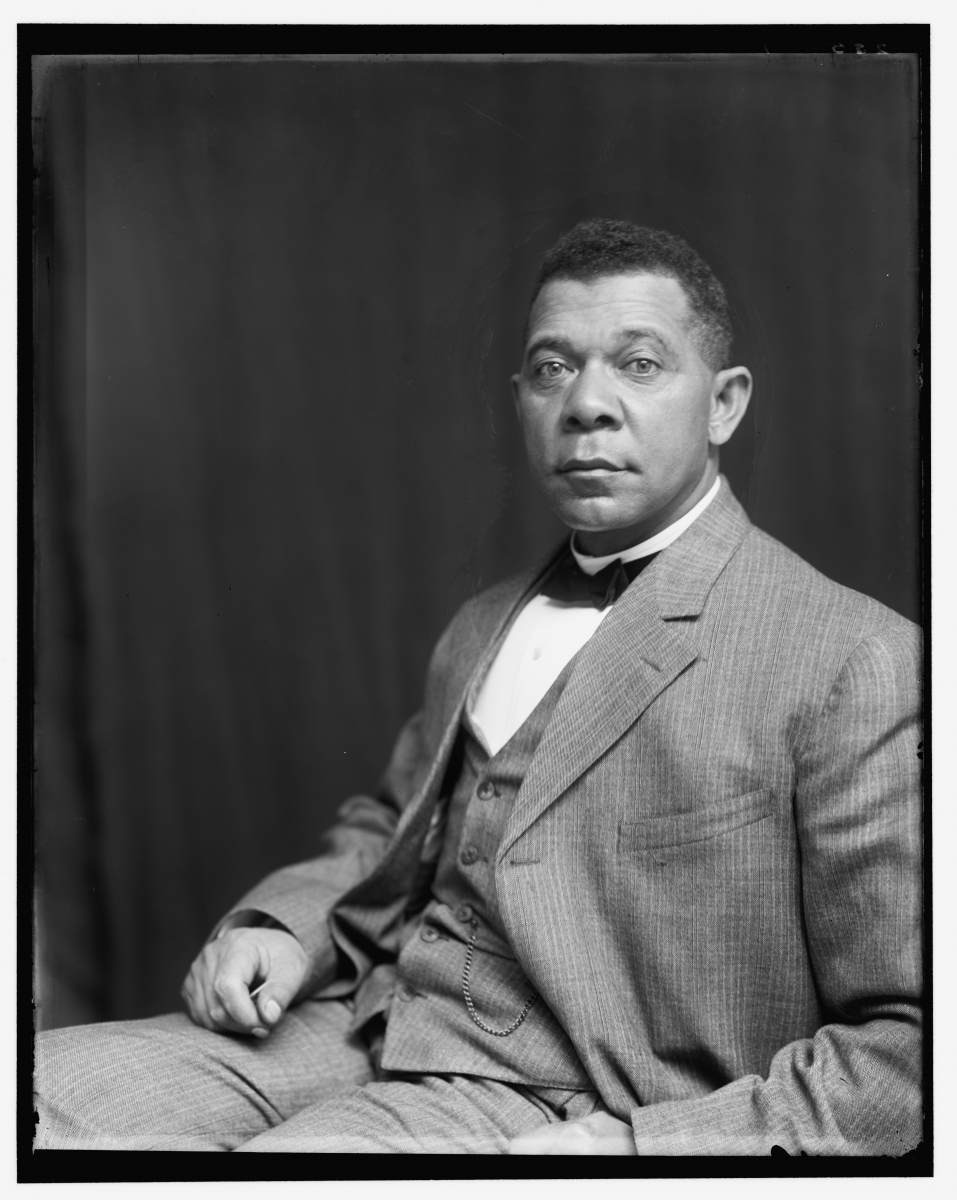

As he delved into the intersection of his trade skills and the wellness mission of this project, the vision behind his book became even more clear. The labor of revitalizing physical health and spiritual wellness within our community will require a change in culture in which introduces through four principles: train daily, pray daily, develop divine character and fast daily. It also struck me how these efforts harmonize with a profound cultural tradition of self-reliance as echoed by luminary Booker T. Washington.

Booker T. Washington was a pioneering educator and leader during the post-Civil War era. He advocated for the economic and educational advancement of African Americans in the United States. Washington founded the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama, a historically Black institution that emphasized vocational training and self-sufficiency, reflecting his philosophy of self-help and practical education for African Americans.

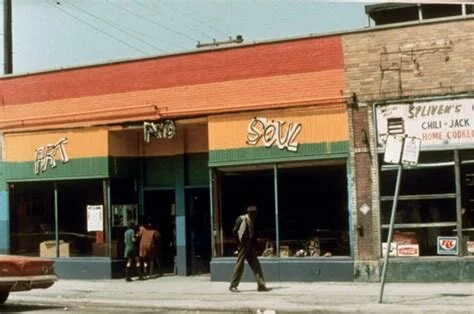

In the fusion of Earthships focus on biotecture and Booker T. Washington's philosophy of building self-reliant Black communities, we unearth an Afrofuturist vision that transcends time, a profound tapestry of innovation and self-reliance, weaving a sustainable future where our community's destiny is beautifully redefined.Our Earthship experience provided not just a shelter but profound inspiration, aligning our pursuit of wellness, self-reliance, and sustainability with a philosophy that transcends walls and roofs, offering a transformative vision for our community's future.